|

OldBoy Palindromes 2046 Jesus Is Magic Brokeback Mountain [FILM COLUMNS OF 2004] [FILM COLUMNS OF 2006] [OTHER HELL FILM WRITING...] |

HELL AT THE MOVIES 2005

Richard Hell's movie column for BlackBook magazine, which appeared 2004-2006

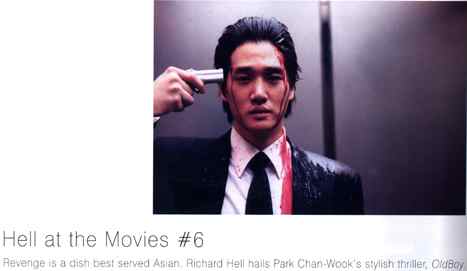

Column #6, Feb/Mar 2005

OldBoy

director: Park Chan-wook; script: Hwang Jo-yun, Lim Jun-hyung, Park Chan-wook, Tsuchiya Garon, Minegishi Nobuaki ; cinematography: Chung Chung-hoon; cast: Choi Min-sik, Yu Ji-tae, Kang Hye-jeong

Is Taxi Driver a revenge film? Is The Searchers? Unforgiven felt like a revenge film. How about Carrie or Elephant? Hamlet is a revenge story. Maybe every drama is either a love story or a revenge story. You either have love or you're very pissed off that you don't. Anyway, revenge is a good pretext for a movie, especially a violent action movie. Such is OldBoy, by the Korean director Park Chan-wook, released here in March after winning the 2004 Grand Prix at Cannes, awarded to the most original film of the year. Quentin Tarantino was the president of the jury and he loved the movie.

I like good action movies and I liked this one. A lot of the best action films (and horror, and annals of lonely glamorous youth) have come out of Asia in recent years. Tarantino's Kill Bills, of course, paid direct homage to Asian martial arts revenge flicks. To name just three directors of international stature whose reputations were made in Hong Kong alone: John Woo (Broken Arrow, Face/Off) is now a successful action director in America; Tsui Hark (Green Snake, Time and Tide), a master genre filmmaker who hasn't really broken through in America (but who was also on that jury at Cannes); and Wong Kar-Wai (Days of Being Wild, Happy Together) whose coolly stylish movies mostly about sad young people have gotten him a worldwide following among that constituency. There are plenty of interesting movies coming out of Japan and mainland China too. Asia is the coming thing. But I digress.

OldBoy is the second film in a revenge trilogy Park has embarked on, though he insists the choice is arbitrary, that he only continued the theme after Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) to please his producer. Park is an interesting case as a genre director. He went to university to study aesthetics as a branch of philosophy with the aim of becoming an art critic, but seeing Hitchcock's Vertigo left him certain he'd regret it forever if he didn't try to make films. "After that," he said, "akin to James Stewart when he was blindly chasing after some mysterious woman, I searched aimlessly for some kind of irrational beauty." (!) His films are wildly inventive. Every scene uses some extreme technique -- whether it's an unusual lens, a color effect, an extreme angle, even animation -- to put across the situation on the screen. You could call it expressionist, maybe, or be petty and call it MTV. But to my mind Park's style is not MTV -- glitzy weirdness for its own sake -- but a genuine grasp of the insane range of filmic techniques available for suggesting emotion.

Despite the director's protests, the vengeance theme does seem appropriate to Park's mentality. His movies are viciously violent. He denies this, as directors usually do ("I didn't show any of that on screen. I never showed the tongue being cut out; the camera moves from the eye to the hand" -- the hand holding the scissor blades pressed to the tongue -- "to the closing of the hand. That's as far as I would go."), while justifying it, as directors also usually do ("I'm often misunderstood as a director who enjoys violence, but really I want to show how violence makes the perpetrator and the victim destroy themselves. I think I give more moral lessons to the audience than Disney!").

Frankly, I'm kind of tired of the continuing one-upmanship in violence and perversity among the recent generation of directors. I think it's become the other side of the coin of sentimentality. The classic definition of sentimentality is "unearned emotion" -- a privileged, unreal, self-indulgence in the sugary sadness of things. There are a lot of recent movies and books I'd call excremental for their unearned disgust -- their privileged, self-satisfied wallowing in the gruesome shittiness of it all. David Fincher is a prime example of an excremental director.

Filmmakers of extreme violence often claim, as Park has, that their work gives "civilized" people an outlet for their rage. Maybe there's some validity to this -- I'm all in favor of pornography as being merciful -- but still I don't think it's exactly something directors can brag about; it doesn't take a lot of skill to trigger either semen or adrenaline. The more reasonable explanation is that the bloody routines are the equivalent of the old-time musicals' competing resourcefulness at dance numbers -- Tarantino being the Fred Astaire of freak atrocity. But I'm ready for the decline of the clever-agony trend.

OldBoy is set in modern Seoul and is about a hapless businessman who becomes a vengeful maiming machine after he is kidnapped and kept prisoner for 15 years for no apparent reason. It's a very adroit and exciting film and I recommend it to everyone who likes a good "movie movie" of the eating-live-octopi and pulling-teeth-with-a-claw-hammer type. The acting is great and there's a little nice sex too.

Column #7, Spring 2005

Palindromes

director: Todd Solondz; script: Todd Solondz; cinematography: Tom Richmond; cast: Emani Sledge, Valerie Shusterov, Hannah Freiman, Rachel Corr, Will Denton, Sharon Wilkins, Shayna Levine, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Ellen Barkin, Stephen Adly Guirgis, Matthew Faber, Debra Monk, Richard Masur

Todd Solondz films are guilty pleasures by definition: their pleasure comes from close attention to everybody's continuous excruciating meannesses to each other, and that "everybody" includes you. Granted, they're meant to make you laugh and they succeed at that, but now even the comedy seems to be getting removed little by little. Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995) was his funniest, most consistent, integrated, film, while the ones that followed, Happiness (1998), Storytelling (2001), and now Palindromes, have each gotten a little more purely acidic, with more and more places in them where the acid burns through, leaving strange-smelling, fuming holes.

The overall bitterness of his movies would seem to indicate that the director was traumatized in youth to find that he wasn't regarded as a magnetic personality. And it's true of him as an artist too: no matter how smart and insightful, Todd Solondz is not a director you love. In every movie he makes there come a few points where you lose your patience, where his focus on hypocrisy, cruelty, and selfishness seems too narrow to carry a film and starts getting tedious. But he always recovers. This new film is the most arduous, with more dicey stretches and the longest wait for a redeeming payoff, but it does end up succeeding, and it's more ambitious than the others in many ways.

Solondz has said all his films are love stories, and there's truth in that -- he's mostly written about people hoping for involvement with other people. It sure has taken him to some funny places, though, such as when 13-year-old wallflower Dawn Weiner in Dollhouse is invited out on a first date by her tight-lipped classmate hero, Brendan, with, "You get raped. Be there." Or in Happiness, when the mild, slightly stunned-looking, psychologist played by Dylan Baker gets exposed as a pedophile, and his pubescent son, with whom he has a caring, honest relationship, asks him tearfully, "Would you ever fuck me," and the father assures him, "No. I'd jerk off instead." Or, in Storytelling, when the small boy of an upper-middle class family finds their housekeeper weeping and, once he draws from her that it's because her grandchild has just been executed for rape, asks, "Consuelo, what is rape exactly?" and she replies, "It's when you love someone and they don't love you and you do something about it."

Lines like these are comic, more or less, but they're not mocking or exploitive the way they might seem in different circumstances. In the movies, they're considerate. Solondz doesn't condemn his characters -- each tends to be mean and innocent equally. That's what keeps the stories interesting. People can't help what they're like. If we could, we'd all be beautiful and popular.

This new movie is Solondz's strangest yet, with very little in it that's laugh-out-loud funny, but more than ever that's taboo. His previous movie, Storytelling, opened with Selma Blair's contorted face and naked upper body writhing and bouncing in erotic abandon atop a sexual partner who, when the camera panned down, turned out to be a guy with his clawlike left forearm pinned to his torso and his mouth pulled sideways by cerebral palsy. Palindromes, for much of its length, seems to be made exclusively of that kind of material (which isn't comedy), while, unlike the Blair "fiction workshop" Storytelling segment (which got pretty brilliant pretty fast), this new film's provocations don't, at first, seem to add up to much.

Palindromes follows the quest of a barely pubescent girl to get pregnant so that she can "have lots and lots of babies, as many as possible, because, um, because that way I always have someone to love." Those words are spoken by a little black girl, Aviva, the lead character, who looks about six, to her mother (Ellen Barkin). In the next scene the same little girl, now white, and a slouching, overweight, expressionless thirteen or so, is on her way with her parents for a friendly visit with another family, the dull young son of which Aviva will promptly induce to impregnate her. (It turns out that the Aviva role, a 13-year-old girl, is played by eight different actors: two grown women, four girls 13-14 years old, one 12-year-old boy, and one six-year-old girl.)

Now that Aviva has become pregnant, she's forced by her parents to get an abortion. In the wake of that medical procedure, the hurt and horrified girl runs away from home. Hitchhiking, she tries to obtain a new pregnancy from a truckdriver whom she follows into his motel room, but disappointingly is provided only anal consummation. The next morning the trucker abandons her. Following this, the exhausted child (in the form, now, of an obese black woman who looks about twenty-five) is taken in by a fundamentalist Christian couple devoted to adopting variously afflicted and congenitally disabled children -- heirs to Down's syndrome, leukemia, missing limbs, epilepsy, cystic fybrosis, etc. -- whom they pamper with love as well as teach to perform fancily choreographed gospel songs for presentation at religious gatherings.

This takes us about halfway through the movie. There's been hardly any comedy and the acting is rudimentary (most of the Avivas are non-actors). The pacing is slow and the story grim to no apparent end. It occured to me at this point that maybe Solondz's reason for the multi-actor role-fill was to complicate things in hopes it might keep our attention. The viewer, drifting and flailing for some kind of grip, also starts to pick up on indications that maybe the film is about our current socio-political situation: Aviva makes up a story about her parents having died in the September 11th attacks, and there's all the screentime for "Born Again" Christians, and constant treatment of abortion matters. So, giving the filmmaker the benefit of the doubt, one wonders if that's why things feel difficult -- that maybe it's supposed to be appropriate to the subject of our ugly times. And I can give him the multi-Aviva's as strictly a thought-stimulant -- it's OK with me...

But, then, what's the "palindrome" angle? There's a character in the film who seems to be its "Greek chorus" commentator, or Solondz-surrogate: Mark Weiner (Matthew Faber), the brother of Dawn Weiner (who was the main character in Welcome to the Dollhouse). Palindromes' opening credit sequence features Mark's funeral eulogy for Dawn. (Who, it turns out, has committed suicide after becoming pregnant as a result of date rape. Aviva is Dawn's cousin.) It's Mark who will introduce the title-subject, asking Aviva as she's leaving home, "Did you know your name is a palindrome... It's a word you spell it backwards and forwards it stays the same, never changes." Mark reappears at the end of the film and elaborates on this theme, of nothing ever changing, etc., in a little philosophical monologue that puts the movie in a fresh light, and for me saves it, making its difficulties seem worth while. That was an unusual experience, to find an "art" movie that seemed mostly failed get its parts clicked into place by some remarks a character makes in its last few minutes, but that's how this film operated for me. As problematic as the movie is, it's that thought-provoking as well.

Column #8, Spring/Summer 2005

2046

director: Wong Kar Wai; script: Wong Kar Wai; cinematographers: Christopher Doyle, Lai Yiu Fai; production design: William Chang Suk Pin; art director: Alfred Yau Wai Ming; cast: Tony Leung Chiu Wai, Gong Li, Takuya Kimura, Faye Wong, Ziyi Zhang, Maggie Cheung

Wong Kar Wai movies are light weight, like smoke, like the sound of rain, like light itself, like this sentence! I really love his new movie, more than any of his others. Some of the earlier ones were more or less boring: Happy Together, In the Mood for Love; or annoying: Fallen Angels; or lovely and moving (if sometimes boring and annoying): Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express; but 2046 is elixir, it's magnificent, the essence of sad, fake-tough gorgeousness, and is not to be missed.

The principal quality of Wong's movies is their visual (and aural) style, and the style is so stylish -- meaning just at the frontiers of where "real life" (fast food joints, crummy apartments, industrial landscapes, sentimental pop music) meets the utmost aestheticization of things (extreme wide angle lens, slow-motion, hand-held camera, highly coordinated color schemes, garish over-exposure, opera, voice-overs) -- and the stylishness is so intense that it overwhelms anything else. It becomes the content in a way that can ultimately feel frustrating because the style keeps saying "this is lovely and fascinating" no matter what's going on: cold slaughter, a lover's indifference, boredom, hopelessness, passionate emotion, locking your father in the bathroom, whatever. Everything is so pretty and chic-looking. Is memory really the chicification of one's personal reality? It has almost seemed like that in Wong Kar Wai. Because his movies are mostly about memory: about loss, transience, and, as a result, hopelessness.

Though I suppose this, this gorgeousness of things in Wong's memorial universe, makes sense. One might well resent being dominated by a traumatic past, but at the same time, why not live in memory -- it's where a person can keep things from changing. It's the place where the consciousness of the romantic, sentimental schoolgirl (possibly living inside the whore) and the haunted lonely tough guy (her lover) intersect: the territory of Wong's movies.

As the director's films increase in number (2046 is his seventh feature since his first, As Tears Go By, seventeen years ago), the sources of his preoccupations and themes become more apparent. Wong is an exile whose movies are suffused with a sense of loss. Born in Shanghai, in Communist China; his family emigrated to Hong Kong when he was five in 1963 (a date featured prominently in his movies), but because of political turmoil his brother and sister were forced to remain behind. In Hong Kong, where his family lived in poverty among other poor Shanghainese immigrants, Wong didn't learn the local language until he was 13. His father was a sailor and later a nightclub manager. Wong spent most of his time with his movie-loving mother. The director seems to have a strange nostalgia for this period in Hong Kong, as the definition both of beauty and of loss. The otherworldliness of his childhood seems to have fixed him in it. Only a kid or a professional killer or a drama queen could take seriously the conception of love his movies purvey (the only love is first love, before love has had a chance to change at all). But you don't have to take it seriously in order to appreciate him, any more than you have to take seriously the emotional preoccupations of Douglas Sirk or Jerry Lewis or Martin Scorcese to appreciate them.

Wong's best work is more like poetry (or painting: collaged and abstract) than it is like stories, but poems that can hold their own with the most affecting pop songs, or the most satisfying crime novels, rather than the cross-eyed soft flowers, sunsets and wistful sweetness often called "poetic." (Though there's plenty of whimsy in Wong -- it's one of the things that can get annoying, though he usually pulls it off.) They're poems in that they make patterns that have the logic of their maker's inner world rather than being cut to fit a pre-existing form, the way movies usually are. On the other hand, strikingly, 2046 is a genre film. Most of Wong's movies have the mood and sensibility of classic "film noir." They're about men who are cynical about romance because they were originally hurt so badly in love, they're about urban alienation, they're about cheap rooms, about casual extreme violence, they're full of rainy streets and darkness and shadows and loneliness and erotic cigarette smoking. 2046 is the apotheosis of these tendencies: it's noir distilled to its essence, without end or beginning.

Also, as in modern poetry or painting (or jazz), Wong makes up his movies as he goes along, and fills them with overlapping quotes and signature references, variations on his themes. He shoots many more scenes than he uses and any story (usually rudimentary) is created by how he edits the results. Neither the actors nor the director know what will happen in the movie until the movie's release. During the making of 2046, it was often described as a science fiction film. There's hardly any of that left. The remnants turn out to be scenes taken from a science fiction story that the film's protagonist, Chow (Tony Leung Chiu Wai), is writing. That story, which is about the year 2046, contains bits and pieces translated from his "real" life (the narrative of the movie we are watching). This, in turn, parallels the way that 2046, the movie, cannibalizes and refers to characters and incidents and data from Wong's previous movies, the same way the movies use Wong's own experience as their source. He does this fractal repetition of motifs and patterns very well -- it doesn't feel contrived, but in fact true-to-life in a genuinely poetic way.

2046 is about the hard-bitten pimplike pulp fiction writer, Chow, in the Singapore of 1963 and the Hong Kong of 1966-69, and his relationships with a series of women. The most prolonged relationship is with the resident of room 2046, Bai Ling (Ziyi Zhang). The charm of the actors can't be overstated. Ziyi Zhang is as unaffectedly, quiveringly sexual as Marilyn Monroe, while as elegant and self-possessed as Audrey Hepburn. Her ordinary speaking voice is sexier than most women's nudity. Tony Leung in this role has been compared by Wong to Clark Gable, but Humphrey Bogart would be just as apt. The look of the movie is breathtaking. There were actually two separate moments when I gasped and felt my eyes start to well, solely in reaction to a shot, an image, distinct from any narrative meaning. I wanted to be part of the culture that wanted from its movies what this movie provides its audience. But, I suppose, by loving the movie, I am part of that culture. And this, in turn, one could say, resembles how Wong in his movies, by longing for evanescent beauty renders it permanent.

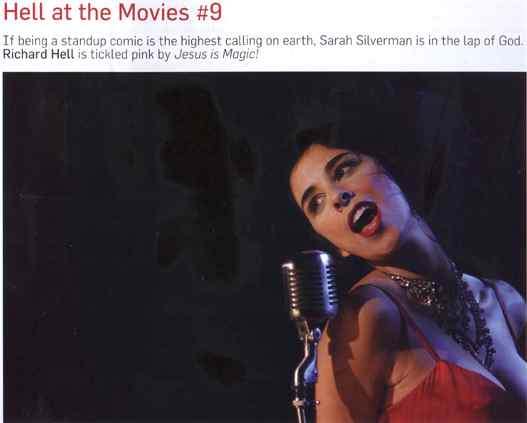

Column #9, Fall 2005

Jesus Is Magic

director: Liam Lynch; script: Sarah Silverman; cast: Sarah Silverman, Bob Odenkirk, Brian Posehn, Laura Silverman

It's occurred to me more than once that I wish I could frame my whole life as a comedy routine. What does this have to do with movies? Well, if if you knew that I intended my whole life as a joke, that question would answer itself. Maybe everybody really has two lives: what they experience as it happens, and then how they experience it in retrospect. The first time is tragedy, the second farce, as Karl Marx put it. Or, as Charlie Chaplin said, life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long shot. Where am I going with this? To Sarah Silverman, and her beautifully coiffed and lilting anus (you have to see the movie). Sarah is so quick that she makes the tragic comic while it's still happening.

But really I do think that to be a standup comic is the highest calling on earth. I'd give anything to be a good comic. I may still try. It's the hardest job in entertainment (slash "art"), and the most satisfying (that feeling you get when you get a laugh). And the good thing is it's really emphemeral, which is admirable, a kind of higher truth in itself (because nothing really lasts). Standup comedy does not survive. Lenny Bruce himself is a trial to sit and listen to at this date. I wonder how much longer Andy Kaufman will stay funny. Maybe he'll be an exception. But for the most part standup is either topical, or gets a lot of juice from attacking the boundaries of propriety, both of which things date fast. Though there are immortal, archetypal jokes. That's what The Aristocrats is about. The jokes are eternal and the comedians are their humble media. (Speaking of The Aristocrats, I thought it was weird that no one commented on the political content of the central joke. The comics who analyzed it got it backwards. The fact that the joke's punch line reveals that a pornographic vaudeville family act of spectacularly bloody and scatological grossness calls itself "The Aristocrats" is funny not because of its stupid inappropriateness, but for the exact opposite reason: its surprising insight. Take Prince Charles--please. Not to mention Paris Hilton.)

But what a beautiful vocation: to show how ridiculous everything is all the time. To make that your whole life and reason for being. And the success-criterion is so clean. It's even more clear-cut than athletics. If you get laughs, you win, if you don't, you lose. I like the mutual-support aspect of it too. Maybe I'm naive, but comics seem like natural, inevitable, support groups for each other, like war veterans or recovering drug addicts. They share an extreme experience which creates a compassion and appreciation for each other that shows in practice (as in The Aristocrats, or the recent Seinfeld standup documentary Comedian, or Broadway Danny Rose). Because, of course, standup does have its dark side. What performance trade is more stressful? It's said that surveys show that the single most anxiety-provoking experience Americans can think of is public speaking, and standup is public speaking to the nth. Which is part of the reason it's as aggressive as it is. To do well is to "kill" the audience. There's the standard explanation for this that the comic is getting back at all the people who've tormented her over the years. But it's also a weird syndrome of the performer resenting the paying audience for taking this position of ruthless judgement, no matter that the crowd's been most fervently and obsequiously solicited by the comic... Anyway, there's a lot of tension and hostility involved.

But back to Sarah Silverman. Normally I wouldn't write about a concert movie, because there isn't much movie to it: you point your cameras at the stage and there it is. But results are what count, and I had a great time at this show. Anyway, films have always been as much about their stars as anything, there's no getting around it. A concert film is a kind of ultimate star vehicle, and Sarah Silverman deserves it. I've had my eye on her for a long time, and she's been around for longer than that. She's thirty-five (though she looks ten years younger) and she actually wrote for and appeared regularly on Saturday Night Live all the way back in their 1993-1994 season. She's had troubles with censors the whole time too. Her first bit on SNL was as a commentator on the "Weekend Update" discussing the twenty-four-hour waiting period for abortions required by certain states: "Quite frankly, I think it's a good law. I was going to get an abortion the other day. I totally wanted an abortion.... And it turns out I was just thirsty." And she is still embarrassing NBC in the new century. Four years ago the network decided to apologize to Asians when there was protest over Silverman's account to Conan O'Brien on Late Night of how she'd wanted to avoid jury duty: "My friend said, 'Why don't you write something inappropriate on the form, like "I hate chinks?" But I didn't want people to think I was racist. So I just filled out the form and I wrote 'I love chinks.'" This is all mild compared to what she does in her stage act, which is what Jesus Is Magic is, though many will know more or less the style to expect from seeing her on the Comedy Central Pamela Anderson Roast in August. She doesn't hold back.

You can't talk about Sarah Silverman without mentioning her appearance. Not only is she wildly lovely, but she has the charismatic immediacy, the physical expressiveness, of a star actress. These things add a nice piquancy to her frequent references to her own asshole. Richard Pryor had similar luck with the way he always looked like a cute nine year old while he was talking about drug-whores and beatings and starvation. Silverman relies a lot on adopting the persona of a ditzy JAP type who does things like authenticate her compassion for 9/11 victims by comparing their plight to the tragedy of her discovery that her daily soy latte actually contained NINE HUNDRED CALORIES. The show goes pretty far out, but Silverman pulls it off, with a bright smile, whether because her ways of mocking attitudes towards 9/11 and AIDS and race-hate work as real insights, or just because she's good enough to say "fuck you" to everybody because she's a bad-ass comedian and fuck you. She overreaches with the four or five musical numbers though. Movie columnists want to be comics and comics want to be pop singers. But she is great and the movie is funny.

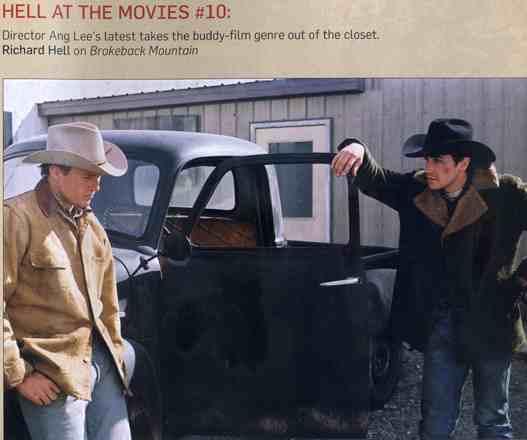

Column #10, Winter 2005/2006

Brokeback Mountain

director: Ang Lee; script: Larry McMurty, Diana Ossana, from a story by Annie Proulx; cinematography: Rodrigo Prieto; cast: Heath Ledger, Jake Gyllenhaal, Randy Quaid, Anne Hathaway, Michelle Williams

Ang Lee makes me think of the old-time Hollywood studios and the tradition of the "quality picture." He's like MGM, as MGM was in the 1930s and '40s, making skillful, classy, affecting films in all genres, set in many periods. In those days, individual directors were that versatile, too. William Wyler is a good example. (Interestingly, he was also, like Lee, an immigrant, from a fairly comfortable family background, arriving in the US in his late teens: Wyler a German Jew from Alsace, Lee a Chinese Taoist from Taiwan.) Wyler won three best director Academy Awards -- exceeded only by John Ford's four -- and made everything from westerns to family dramas to musicals. He was a great director of actors, too, helping boost to stardom many Hollywood legends -- Humphrey Bogart and "the Dead End kids" in Dead End (1937); Henry Fonda in Jezebel (1938); Laurence Olivier in Wuthering Heights (1939); Montgomery Clift in The Heiress (1949); Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday (1953); and Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl (1968) -- all in excellent movies that betrayed no identifiable director's personality or "touch."

So, as unusual as it is in these days of specialization and auteur consciousness, there's plenty of precedent for global, near-anonymous skill. Which isn't to say Ang Lee's talents aren't impressive. I've always liked his movies a lot: The Wedding Banquet (1993, a comedy about gay Chinese-American immigrants), Sense and Sensibility (1995, late 19th century Britain -- Jane Austen -- more or less introducing Kate Winslet), Ice Storm (1997, perceptive, intimate description of weird cold upper-middle-class 1970s American suburbia, introducing Tobey McGuire), Ride With the Devil (1999, Midwestern Civil War pic), and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000, period Chinese martial arts flick, introducing Ziyi Zhang). The Hulk was the exception that proved the rule of his ultra-competence. Now, people are talking Academy Awards for Lee's new film, Brokeback Mountain (Crouching Tiger won four, including best foreign language film). It's already won the Golden Lion, the top award at the Venice Film Festival.

Brokeback is about the love affair between a couple of cowboys in Wyoming between 1963 and 1983. On one level, it's a classic (or "ordinary") story of an affair between two people who can't let their relationship be known, whether because it's adulterous or because it defies cultural taboos -- racial, political, or whatever. On the other hand, any kind of depiction of gay love that's not essentially comedic is a pretty new thing in a mainstream American movie.

It seems to me that the first thing to be noted about how these two cowboys are portrayed is that neither of them is ever shown to be effeminate at all. In a way, I suppose, that's progressive, but there are other things about the lead characters that make me wonder whether their "romantic" love is actually "gay" in essence. Maybe that's the point: that the dividing line between "gay" and "straight" is elusive or even nonexistent. Both men get married and have children, too. But you get the feeling that these men's backgrounds are so emotionally impoverished that they're both stuck at a barely adolescent stage, or at least a place where they're more at ease with men than women -- the way a lot of boys and men are in fact. Often that's actually thought of as a "macho" trait! It's funny. The film is like a buddy movie that goes that one extra step. Nothing we're shown about them suggests that their relationship differs much from that of any two guys who like to go hunting and fishing and drinking together -- except that these two just happen not to mind actively assisting in each others ejaculations. Of course, the problem is that, where they live, such behavior can get a person bludgeoned to death by the more sexually insecure he-men in the area. (As in Academy Award-winning Boys Don't Cry.)

The film is as satisfying in its presentation of a cultural milieu as Lee's various other movies have been. The details of the leftover-cowboy purlieus of backwater Wyoming and Texas -- omnipresent huge sky, broke-down trailer offices, small-town rodeo queens, half-dead ranch operations, swaggering farm-machinery salesman as patriarchal success story, etc., and the dominating interludes of sheep-herding and camping in the wild mountains -- are all seductively handsome and realistic.

The script was written by Texan Larry McMurtry, author of such novels as Lonesome Dove and The Last Picture Show, and his writing partner, Diana Ossana. They were faithful to the convincing West of Annie Proulx's original short story, which has been much admired and talked about since it appeared in The New Yorker in 1997. Nearly all the dialogue published in Proulx's story was kept in the movie, for obvious reasons ("Tell you what, you got a get up a dozen times in the night there over them coyotes. Happy to switch but give you warnin I can't cook worth a shit. Pretty good with a can opener.").

The acting and casting are superb. I won't be surprised if Heath Ledger receives an Academy Award for his Gary Cooper-to-the-point-of-autism version of a close-mouthed but lustful fucker of Jake Gyllenhaal's lonesome butt. It's the kind of thing the Academy does award. These actors were pretty brave. The recurring image that remains for me is a brief shot of Jake's frightened and amazed but grateful face as he first takes it on his hands and knees from Heath up behind him in a tent. This is what people will be paying to see. Not really. People would go to this movie if Jake was a girl, too. The picture has those classic good-movie qualities that have made the other Lee flicks worth seeing (great art direction not least among them). Though I have to say that, while his soundtrack music has always been pretty conventional, I found it positively irritating in this -- being mostly spare, pretty, wistful-sounding acoustic guitar-picking meant to signal romantic sadness and nostalgia. Ugh...

But, to repeat, I've always liked Ang Lee. I respect his intelligence and professionalism and skill and have even appreciated the near-invisibility of personality in his filmmaking -- I think there's explicitly something of the values of the Tao (pre-Zen Chinese philosophy) in it, which is an intriguing twist to the Goldwyn-Mayer-Thalberg principal of high-class entertainment (as opposed to "self expression"). And this movie has all those virtues, plus the intrigue and novelty-value (or what have you) of watching two manly movie-star cowboys making out. So that's a pretty good deal.

The above review prokoved the following exchange -- a letter from a reader, and response to that letter from Richard (which were published in BlackBook #44), and then a follow-up response from the original letter-writer:

Dear Lustful Fucker (via Richard Hell),

Your review of Brokeback Mountain was amazingly appalling. Thank you very much for summarizing a loving relationship between two men as one that was like any other buddy friendship between two men. They are in love and it is OBVIOUS that they are. You might have missed it while you were busy thinking up those awful gay butt jokes for your review. Saying gay male relationships are straight male friendships with the exception that gay males 'just happen' to like to lend a hand in getting each other to ejaculate, is not humorous, it is demeaning. The sentence 'these two just happen not to mind actively assisting in each other's ejaculations' is one of the worst things I have read about a gay relationship. While I assume the unbelievably passive and impersonal voice is your attempt to look like a dry witty fellow it is a disaster and really devalues your praise of the movie.

But I also want to thank you for stating that their impoverished lives left them at a stage where they are more likely to go to a male for emotional and physical love, a stage called prepubescence! You managed to include two major classic arguments against queer culture in your article; that queers are driven by happening, once again I will quote this awesome sentence of yours, 'to not mind actively assisting in each other's ejaculations' and their emotional and/or mental immaturity. Ugh!

diana parker

Outreach Specialist

LGBT Campus Center

UW-Madison

Madison, WI

Dear Diana Parker,

I apologize. I sure don't want to contribute to discrimination against gay people. I didn't know about the "classic" argument used to belittle or dismiss "queer culture" that portrays gayness as being some kind of stunted emotional development. My comment in my review was a direct reaction to the movie itself, in which we are shown vividly and explicitly how cold and how mean both the cowboy lovers' childhoods had been. In fact the movie could almost be interpreted as much as a portrait of Ennis Delmar's emotional unavailability (except to a bloody shirt) as as any kind of "love story." On the other hand, maybe you did detect some offensive, ignorant, unfair misconception I have of possible varieties of gay psychology. I ain't perfect. I think you're pretty harsh, but I concede that in matters like this, you, being, presumably (given your position in a lesbian gay bisexual transgender campus center), the gay one, have rights I don't. I would point out though that I feel about homosexuality the same way as the main character in my novel Go Now, Billy Mud, who, when asked whether he'd like to make love with men, said, "I get so into my own cock. I don't know why I couldn't get into someone else's." Regarding the friendly-ejaculation-assistance remark, what I wrote about the lovers there was in the context of describing the movie too. It was, "Nothing we're shown about them suggests that their relationship differs much from that of any two guys who like to go hunting and fishing and drinking together--except that these two just happen not to mind actively assisting in each others ejaculations." (Note the "Nothing we're shown.") I agree I went too far with that though. Ang Lee did show Ennis throwing up (or whatever it was) when he had to act casual about parting with his lover (personally, I had kind of a hard time buying that bit), and there was that pretty extreme reunion embrace spied by Ennis's wife. So I was being a wise guy. But I'm not sure what the relationship between love (of whatever intensity or flavor) and sex is in romantic liaisons between people of any shade of sexual preference. Obviously, it's various and complicated. Still, that was the straightest gay couple I ever saw. The question I was asking is, what are the implications of that? I thought it was kind of Hollywood.

Best,

Richard Hell

film critic, BlackBook

New York City

Richard Hell,

Thank you for your response to my scathing email. I admit it was rather harsh and I failed to mention that I agreed with you on some points. I don't even really like the film. But I do agree with your response that that was the straightest gay couple I've ever seen and the implications are many and complicated. That being said, I loved your review of 2046...a current visual and auditory obsession of mine.

Keep on..and I'll try being nicer.

Diana Parker