|

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind Non-Hollywood Movies Tarnation I [Heart] Huckabees Notre Musique [FILM COLUMNS OF 2005] [FILM COLUMNS OF 2006] [OTHER HELL FILM WRITING...] |

HELL AT THE MOVIES 2004

Richard Hell's movie column for BlackBook magazine, which appeared 2004-2006

Column #1, Spring 2004

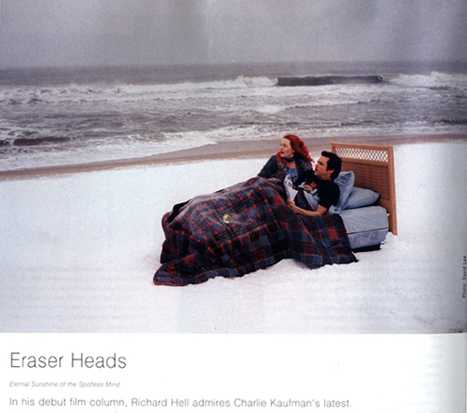

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

director: Michel Gondry; script: Charlie Kaufman; cinematography: Ellen Kuras; cast: Jim Carrey, Kate Winslet, Kirsten Dunst, Tom Wilkinson, Elijah Wood, Mark Ruffalo, David Cross

The hype about Charlie Kaufman's mind-blowing scripts has kind of put me off. There've been four filmed in the five years prior to this one: Being John Malkovich, Human Nature, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, and Adaptation. His high-concept mind-mixed-with-"reality" stories are not as shockingly original as they're sometimes made out to be. I know he himself would acknowledge this because he's copped to a weakness for 20th century writers who've explored a lot of that territory -- Stanislaw Lem (author of Solaris) and Kafka (whose most famous work of course is about a man who wakes up as an insect) and Philip K. Dick (source of Blade Runner and Total Recall and Paycheck, etc.), for instance. Kaufman's self-consciousness, carried to neurotic extremes of self-reference in Adaptation, is also common in literature (and in adventurous filmmaking like Fellini's 8 1/2, and nearly all of Godard).

But as I say, Kaufman shouldn't be held responsible for the inflated claims of his wildest enthusiasts. And the last couple of his movies have made me a believer. The guy has really got balls for one thing, as full of self-doubt as he keeps reminding us he is. Courage is often what sets the first-rate apart. You've got to be willing to trust your instincts and go past the frontiers of convention, not faltering, even when the convention becomes "going beyond convention" and you find yourself feeling morally obliged to go beyond the convention of "going beyond convention," and then beyond even that and in fact do falter and then push through that and maybe make a complete fool of yourself. "Woo hoo!" Another thing that separates Kaufman from the rest is that most of the other recent mind/reality meld movies use their premises (What if you were to find out you were not human? What if "reality" was actually a creation manipulated by unknown outsiders?) in the service of typical mystery/suspense/thriller shoot-em-ups, while Kaufman's scripts are about confused and complicated real people getting psychologically and emotionally exposed in the course of the conceptual switchbacks. And of course he's really funny too and I'll get to that in a minute. Granted, the movies have dull spots, and irritating ones, and logic-holes but that's almost inevitable when you're working on the edge. It's worth it (and the possibility also remains that at some future viewing one of the dull spots could turn out to be brilliant).

Michel Gondry has directed one feature film prior to this one -- the mildly excruciating Human Nature. He comes from being a music video whiz (as did Spike Jonze, whose first two movies were also written by Kaufman). Gondry made the amazing White Stripes Lego clip ("Fell in Love With a Girl") and their "Hardest Button to Button" (where each beat creates another identical drumkit/amp/mic across the landscape) as well as lots of famous Bjork extravaganzas. Music videos are basically ads and they tend to be flashy and slick -- even when straining to be "dark" like the obscene David Fincher -- and charming (read "decorative"), but Gondry is well suited to direct The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. His videos are full of loops and multiples and people sleeping and vehicles, all of which figure strongly in this flick. In fact the Kaufmanesque original idea for the film was actually Gondry's. It's about a guy, Joel Barish (Jim Carrey), whose relationship with his girlfriend, Clementine Kruczynski (Kate Winslet), has been disintegrating when he discovers that it's worse than he realized: she has deliberately had him erased from her mind. This pains Joel so much that he resolves to do the same to his consciousness of her, but as he's undergoing the procedure he realizes that despite everything he doesn't want to forget her. Most of the movie is spent in his brain as we trace back his memories of her and he starts trying to hang on to her by hiding her in unlikely recollections where the professional memory-removers won't know to look.

I'm way into Jim Carrey. I've liked him since Ace Ventura, Dumb and Dumber, and The Mask -- his amazing triple-stage 1994 star-birth -- through the transcendent Cable Guy (thank you, Ben Stiller). He's made a few dubious flicks since but he's genius for sure. In this movie he does his "insecure little- guy" schtick, a whole lot of which is terrible posture, and it works OK. It's not what you most hope for from him, and it can seem unreal because so much of him says "over-the-top comic star" no matter how much he tries to make you forget it, but you're still happy to watch him.

Kate Winslet is ravishing. I boycotted Titanic and have somehow, possibly defensively -- she's so attractive it hurts -- stayed out of her way otherwise. What a girl. That smile kills me, the way it looks almost like a grimace at first and then apologetic and then vulnerable, and then heartbreaking, stretched there au naturel across her super-pale but orgasmically flushed face. Again, the only problem is that she's a bit too appealing for the role. Here I blame the filmmakers: there's not enough story info to make her supposedly tawdry, self-hating, personality believable. It's like she's an angelically radiant, smart, spontaneous Kate Winslet going around with a placard hanging from her neck that says "alcoholic slut."

As I was saying, Kaufman scripts are really funny too and a lot of the humor comes from how imaginative and perceptive he is in how he plays out his trippy premises. Gondry is good at executing this stuff. Music videos are ideal training grounds for ways of expressing in imagery states of consciousness and emotions. For instance probably my favorite passages of Sunshine are these bizarre ecstatic scenes when Joel sneaks Clementine into his childhood. There's this one where he's an 18 inch tall infant (Carrey and big furniture) playing underneath the table in the bright idyllic '60s kitchen where his young mother is puttering around and then there's Kate Winslet too, the same age -- and full size -- as his mother, but she has her punkette day-glo streaked hair, and she's so thrilled to find herself there and she's so desireable and she lifts up the front of her skirt for little Jim! That scene alone is worth the price of admission. The film works. It's good. It actually moved me and I didn't expect that.

Column #2, Summer 2004

Non-Hollywood Movies [The Criterion Collection]

I like the theme of this issue [travel]. As William Burroughs paraphrased Pompey, "It is necessary to travel. It is not necessary to live." This is true of the movie-watcher too. To be stranded in Hollywood is almost worse than death. In our films, America presents pretty much the same pumped-up corpus as it does politically: smug, arrogant money-and-power sans inspiration, insight, or grace. So fly, my darlings...

Of course, the kind of travel we're talking about is not first-class travel to luxury hotels in order to regard the foreign culture as a weird curiosity. I didn't like Lost in Translation. Sofia Coppola's world view is that of a bright, highly entitled, sentimental (in the world-weary way of a 15-year-old) preppy girl. The flick had its charm, but I think a few weeks in Detroit without credit cards or phone privileges would have had a more enlightening effect on her.

Don't get me wrong. I love a good escapist movie (in fact, my favorite kind of movies is genre movies that have dimension, like David Cronenberg's The Fly, or Jean-Pierre Melville's gangster flicks, or Doris Wishman's Let Me Die a Woman), and there are plenty of commercial American directors who are profoundly fine: Sofia's father, for one, and Ang Lee (actually, or originally, Chinese), and John Woo (ditto) and such somewhat less crowd-pleasing ones as Cronenberg (originally Canadian) and David Lynch, as well as a lot of American independents whose films one shouldn't miss, like Todd Solondz (Welcome to the Dollhouse), Todd Haynes, David O. Russell (Three Kings), Jim Jarmusch. The American I know of who's really making genius movies now is Harmony Korine (Gummo and Julien Donkey Boy). I hope he can keep his head above water.

The problem with bad (read: typical) Hollywood movies is not that they're empty but that they're cynically or at least ineptly false and manipulative. It's like the difference between good and bad recreational sex. There's nothing wrong with having sex strictly for fun, but at minimum, you should be good at it, and, more important, you shouldn't mislead your partner about what your purposes are, or else it might not just be "empty" but evil (like David Fincher). That would be known as fucking someone over. The worst Hollywood movies are the ones that aren't honestly inviting us in for a shared good time (thrills perhaps) but are sleazily pretending to, i.e., telling us how smart and sexy we are while they're actually picking our pockets.

The great living director whose values are most opposed to Hollywood is French/Swiss: the notorious Jean-Luc Godard. Ironically, he first made his name -- as a critic -- in the 1950s with his brilliant filmzine prose-poems of praise for such semi-anonymous American studio directors as Frank Tashlin, Nicholas Ray, and Sam Fuller. But times have changed. The battles that Godard, Truffaut, Rivette, and co. fought back then to gain respect for the artistry of U.S. genre directors have been won, and the result is, as Truffaut pointed out, that now "more often it happens that though the ambitions of filmmakers are very high their execution can't keep up with them." Yes, the directors are all supposed to be artists now, and the result is horrors like Schindler's List and the propensity of critics to call a movie like Mystic River a masterpiece, just because it's about another serious social subject (child abuse in this instance), shot in grimy working-class locations (Spielberg's equivalent was to go black and white), and rigged with plenty of opportunities for actors to emote. People don't emote in Godard movies. They talk and kiss and recite and read and often die, in the service of the director and the framed image, but they don't "act." And there are no special effects and no blood (there's "blood" in Godard, but, as he pointed out, it's not blood but "red") and no sets, only locations. His films are alive -- rather than being contrived to elicit the viewer's bodily fluids the way junk food's sugar and fat seduce you into obesity.

I don't have the space to go into detail regarding the marvels of Godard, not to mention the movies of other, younger, genius directors in distant places, such as, say, Hou Hsiao-hsien (Chinese, Flowers of Shanghai), Bela Tarr (Hungarian, the astounding Satantango), or Abbas Kiarostami (Iranian, A Taste of Cherry). And anyway, there are few cities in the United States where these movies can be seen in theaters. That's where the DVD comes in. DVDs have made such a difference in watching movies at home, especially when the transfers from film are done conscientiously, using the correct aspect ratio, and carefully restored if necessary. The inclusion of supplementary material (interviews, commentary, trailers, etc.) is great, too. The Criterion Collection pioneered in all these areas, and Criterion's selection of films on DVD is near impeccable. They carry a beautiful handful of Godards (the new Contempt is a bonanza), Kiarostami, Tarkovsky, the ineffable Robert Bresson, and many other such pointedly non-American masters. Tarr's Satantango hasn't been released on DVD (others of his films are out from Artificial Eye, a British company). There's a highly regarded new set of four early Hou Hsiao-hsien flicks from Sino-Movie (Taiwanese but supplying English subtitles). If buying, I'd recommend shopping online, where for instance DVD Planet generally offers the Criterion discs at $26, which is 35% off the list price (do a "title" search for Criterion). Criterion itself has a site where you can find detailed descriptions of their releases.

I want to add a small list of disclaimers: 1) I'm grateful to be an American; 2) I love Bill Murray; 3) Clint Eastwood has probably starred in more great movies than anyone alive, and he has directed quite a few of them; 4) I have no commercial interest in or connection to Criterion or DVD Planet.

Column #3, Fall 2004

Tarnation

director: Jonathan Caouette; script: Jonathan Caouette; cinematography: Jonathan Caouette; cast: Jonathan Caouette, Renee LeBlanc, David Sanin Paz, Rosemary Davis, Adolph Davis

What do gayness, youth, wide-open sex, poverty, mental problems, despair, cruelty, silly drama, and cheesy pop culture have in common? Besides inherent fascination... No maybe it is inherent fascination that's the link: the allure that creates the market for exploitation tabloids. Because there is definitely a kind of tabloid, sensationalist, element in the pleasure to be found in the small quasi-genre of films from the last fifteen or twenty years I'm thinking of, the content of which more or less corresponds to the above list. But these films I'm thinking of are also the most interesting films being made these days whatever their "sensational" subject matter may or may not have to do with it. Other qualities they share are that they're usually played by non-actors and are made extremely cheaply. Harmony Korine's Gummo (1997) is the archetypal masterpiece of the trend, but that's a dumb thing to say. This set of movies doesn't derive from Gummo -- they just have certain things in common with it, and Gummo is the most bountiful of them so far. Some films that belong preceded Gummo too, for instance Todd Haynes's amazing Superstar: the Karen Carpenter Story (1987) (in which the non-actor performers are actually Ken and Barbie dolls). The original models would probably be Andy Warhol's movies and maybe Jack Smith's -- even Bresson, at a certain remove (John Waters is too much parody though his heart's in the right place).

The film that set off these thoughts is Tarnation, a movie concocted by 31-year-old Jonathan Caouette from his collection of mostly home-produced media, reaching back to the first videos he shot at the age of nine in Houston, where he grew up, and earlier than that for snapshots and imagery copped from mass culture, and extending, through answering-machine tapes and pop music clips, up to digital video shot recently in the Queens apartment where he now lives. The entire construction of the movie was accomplished by feeding the raw data into his boyfriend's Macintosh computer and manipulating it with the Apple iMovie editing software that comes preinstalled on Macs. The press release lists the budget for the film at $218. (This doesn't include the multi-thousand dollar cost of converting the Mac-burnt DVD into 35 mm film, or the rights to songs on the soundtrack, or the expenses of accumulating the archive over decades, but it's a valid way of describing the cost of making the film.) It's billed as a documentary, but it reads more like a diary or memoir. It's the revery of his own life by a person who grew up unsupervised, a small child abandoned to foster care, abused, witness to his mother's rape, reclaimed, and gay in Texas, not knowing his father, and whose glamorous heartbreaking mom was deranged, largely as a result of the countless shock treatments she received with the approval of her parents... The kid/filmmaker himself ends up with what he describes as "depersonalization disorder, which is defined as a feeling of disconnection from the body and a constant state of unreality," though I'll be so presumptuous as to say that he doesn't seem crazier to me than half the people I've known. And the film is by no means merely squalid or melodramatic -- it's smart and pretty and fast. One thing for sure is that Caouette is a born filmmaker, as well as a born actor.

Those clips he uses aren't ordinary home movies of course. Then again maybe they are, in the same sense that part of what's so interesting and satisfying about the films I'm talking about is, wait... I'm tired of saying "the films I'm talking about" -- can I come up with a name? ...I'll call them... Candy-Acid... Candy-Asséd... Candy-Assid movies. Part of what's so interesting about the Candy-Assid movies is that they depict what is actually the real present, the real America, of junk-strewn tract houses and cheap motels and PCP and speed and multidimensional sex and nonstop television and franchise businesses and sudden violence and bad health. And they give us that as an environment, not a "subject." And they are exciting, colorful, and moving, as well as often funny. And boring sometimes, but that's because they're about real life. I'd count Bruno Dumont's Twenty-Nine Palms as Candy-Assid too, and it's neither gay nor especially coming from trash culture, but is very boring in the most compelling way. The leads don't "act," hardly anything happens (though the mundane imagery looks glorious), there are gas stations and motels, and the movie seems like unmitigated life: just that boring and shocking. Twenty-Nine Palms is the movie of these most clearly descended from Bresson, who was the original genius of the non-actor in everyday situations shown sublime. Gus Van Sant's Elephant is another Candy-Assid high achievement (and in fact Van Sant came onto the production team of Tarnation once it was made, as "executive producer" to help get it distributed).

Tarnation includes sequences that on their own would blow anyone's mind. For instance a couple of scenes Caouette shot when he was eleven years old, with a stationary video camera, alone in his room, of himself uncannily embodying a distraught female hillbilly testifying, as she nervously tugs at a forelock, that, to start off, "Jimmy says when I wear too much makeup it makes me look like a whore..." I asked the director about this, and he told me he was imitating his mother whose second husband had been beating her up. The sequence ends with eleven-year-old Jonathan-as-Renee lisping, "I blew his ass away." Caouette tells me he'd also been watching earlier that day (twenty years ago) an episode of "Bionic Woman" that featured Lindsay Wagner cloned and imprisoned and that she'd always reminded him of his mother, and that furthermore later the same night he'd seen a PBS broadcast of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf with Alfre Woodard and he probably got some ideas from both. So we have an 11-year-old boy in drag filming himself acting his hysterical mother, using inspiration from "Bionic Woman" and Ntozake Shange. The whole movie is as trippy and chilling and endearing as that. And I swear his pre-adolescent acting is the equal of Brando. But, and this is important, the main thing is that the movie truly feels like everybody's real life. In this time and place, as I suspect in most other times and places, people's actual lives are as screwy as these movies. (It's only the really perverse people in the ad agencies and political campaigns and bible groups who try to pretend otherwise.) And this is just five minutes of the movie I'm talking about. Just as significant are the moody, gorgeous montages cut to evocative pop music that alternate with what Caouette calls the "verité." The film is a knockout. If it plays anywhere near you, you should go see it. (Then make one yourself.)

Column #4, Oct/Nov 2004

I [Heart] Huckabees

director: David O. Russell; script: David O. Russell, Jeff Baena; cinematography: Peter Deming; cast: Jason Schwartzman, Isabelle Huppert, Dustin Hoffman, Lily Tomlin, Jude Law, Mark Wahlberg, Naomi Watts

![still from I [HEART] HUCKABEES](images/Col4.jpg)

I've come across two previous working titles for the comedy that was released as I [Heart] Huckabees. One was Paramus and the other The Existential Detectives. Why did they go with the mystifying bumper sticker? Either of the others seems more appropriate. The final title actually works less well after you've seen the movie than before. Before, it was at least provocative; after it seems gratuitously off-kilter. What's going on? An existential conundrum.

I'm a fan of David O. Russell, writer/director of the movie. I've liked all three of his previous films, each a comedy. First came the jawdropping Spanking the Monkey (1994), which used a suburban middle-class mother-son summer fling (full-blown incest) in the service of a "coming of age" plot and did it in a way that was not only funny but actually believable. The performances were perfect too, though none of the actors was known nor seems to have showed up since -- which'd incline one to give the director a lot of credit for them. The script nailed behavior with the skill of a good novelist. Altogether it was an outrageously strong debut.

Then he widened out in Flirting With Disaster (1996) with a wild range of characters -- the equal of a Coen brothers movie -- from a San Diego Reaganite matron to a sleazy redneck Michigan truckdriver to a pair of leftover hippies running a cottage LSD industry out of their desert basement. The story was about a young guy (Ben Stiller) who had grown up adopted and decides to track down his biological parents. It was just as funny as Spanking, if -- unlikely as it might sound -- more exaggerated a story.

Three Kings was funny too, and it did more new things. It was a combination Desert Storm war picture and heist flick set in Iraq just after the Americans had chased Hussein's army out of Kuwait. Like Russell's previous movies, it seemed like a revelation: original and smart and not predicted by anything he'd done before. It used a lot of flashy techniques -- from a darkroom film-treatment that gave the desert imagery a bleached-out look, to shots depicting the paths of bullets inside bodies -- but they didn't seem MTV-gratuitous. Most surprisingly, the movie was a pretty complex critique of American policy. In fact, it's been announced for re-release now because of its relevance to our current Iraq situation. It opposed both Saddam and George H. W. Bush, but sharply pointed out Bush's oil-money self-interest in choosing that battle from among all the injustices around the globe to send soldiers to fight. Primarily, though, it was highly entertaining.

These movies are so disparate, it's interesting to learn how they're united by roots in Russell's own experience. He grew up in the lockjawed, highly groomed world of Spanking the Monkey, in Larchmont, New York. He studied literature and political science at Amherst twenty-five years ago and originally wanted to write novels. (Robert Stone and Thomas Pynchon were favorites.) His sister was an adopted child whose search for her biological parents inspired Flirting With Disaster. He came to filmmaking relatively late -- he was thirty-five when Spanking was released -- partly because he first spent nearly ten years trying to improve the world more directly. On college graduation, in 1982, he went to Nicaragua, excited about the Sandinista revolt against a Reagan-supported dictatorship. After Nicaragua, he returned to New England and worked variously teaching immigrants English, organizing to improve low income housing, and fighting toxic waste disposition practices. After six or eight years he burnt out on full-time political activism and decided to try filmmaking. Both his political urges and his frustrations about them seem to have survived into his films. It's the comedic treatment of this conflict that provides the substance of I [Heart] Huckabees.

I [Heart] Huckabees is about a kid in his twenties (Jason Schwartzman) who is suffering an existential crisis. It opens promisingly with Albert (Schwartzman) violently cursing on the soundtrack as the blurry screen focuses in to show him wandering through a wild green marsh tormenting himself about what, if anything, is worth doing in life. He comes to a rock and reads a short poem to it ("nobody sits like this rock sits"), addressing a small environmental group that is gathered there. Next thing you know he's rushing through white hallways in search of the offices of the Existential Detectives (Lily Tomlin and Dustin Hoffman as husband and wife). The cheerful Detectives are in the business of shadowing their clients (bathroom visits included) to determine why they are mixed up and then explaining to them how to correct their perceptions of reality.

Albert has founded the Open Spaces Coalition to oppose the plans of a huge department store, Huckabees, to build on the local wetlands. Albert's nemesis is Brad (Jude Law), an ambitious young Huckabee's employee who has charmed the protestors away from Albert by offering Shania Twain as an alternative to poetry and pointing out that the best way to save the wetlands is to own them, as the corporation desires. This is all making Albert crazy. On top of everything, it seems like the universe is sending him secret messages via a recent series of bizarre coincidences in his life. It's too much to deal with. He needs some strong new metaphysics.

Other major characters in the movie are Dawn Campbell (Naomi Watts), the official Miss Huckabees, a writhing hot-panted spokesmodel who is Brad's girlfriend; Tommy (Mark Wahlberg), another client of the Detectives whom they assign to Albert as his "other," a kind of existential-improvement buddy for the duration; and Caterine Vauban (Isabelle Huppert), the dark French philosophical opposition (motto: "Cruelty Manipulation Meaninglessness") vying with the sunnier, more Zen-like Detectives for the inner being of Albert and Tommy.

Does this all sound kind of strained? I'm afraid it feels that way in the theater too. Jason Schwartzman was terrific in Rushmore and all the rest of the cast are people you'd expect to enjoy in Russell's hands, but the movie doesn't come off. It's like listening to a depressed new-age person who's had too much therapy thinking aloud through his insomnia. The filmmaker's aim seems to have been to be funny like self-doubting Woody Allen and conceptually free like reality-bending Charlie Kaufman, but it adds up to a lot of repetitive one-liners about the meaning of things that cancel each other out while the viewer's mind wanders. It's hard to distinguish what Russell's satirizing from what he's actually proposing as important. I believe in supporting artists who are taking interesting chances and for that reason I wouldn't want to miss a David O. Russell movie. I hope you feel the same way, but I have to warn you this one's an existential dilemma.

Column #5, Dec 2004 / Jan 2005

Notre Musique

director: Jean-Luc Godard; script: Jean-Luc Godard; cinematography: Julien Hirsch; cast: Sarah Adler, Nade Dieu, Rony Kramer, Simon Eine; as themselves: Jean-Luc Godard, Mahmoud Darwich

I'm a little embarrassed to be writing about Godard since I promote him incidentally all the time already. I should use the little space I have here to talk up directors more in need of attention. Godard is probably the most written-about director alive. People used to call the Rolling Stones the greatest rock and roll band in the world and, though the loudest of those people were probably hired by the band, still, it probably was true for a couple of years. Well, Godard has actually been the greatest filmmaker in the world since about 1959. (Though, granted, Bresson and Hitchcock -- thirty years his elders -- overlapped him a little.) I know it's wrong to call any one artist the best, but Godard is in a class with Picasso or Bob Dylan for childishly too-much talent and vision exercised through phase after phase into great old age. And, what can I say, his new movie is the best one I've seen this season.

Godard's late films (he's 73 and has made more than 30 features) are the work of an old man in only the best senses: he's been around the block; is death-conscious -- tending in mood to the contemplative bleak -- ; impatient with vanity, inanity, and deception; and crazy with insight. He's also often clownish. Most importantly, he knows how to get celluloid to do about anything he could ever want it to, and his recent movies are as stoked with ideas and spirit as his earliest ones were. Maybe his endless inspiration comes partly from his approach to artmaking, one he also shares with Picasso and Dylan and for that matter Frank O'Hara, and that's that he makes works like superior notebooks. He goes on nerve. Since he's obsessed with cinema, his compositions are as full of filmmaking ideas as they are about whatever else he's feeling or thinking or fantasizing, but he knocks out his movies the way other people talk on the phone or write email or keep journals. This means he's prolific, but it doesn't mean the works are thin: he's prolific vertically as well as horizontally. There are almost always four or five interesting threads and levels happening at once in a Godard movie, so even his weakest moments have something worthwhile going on if you're willing to shift. Sometimes he'll do something just to see what happens if he tries it (and/or to keep conscious that it's "only a movie"). This brings to mind probably the most famous instance of Godard's inspired nonchalance: the jump cuts in Breathless. That innovation -- the removal of frames from the middle of shots, resulting in the stuttering jump of an action from one moment to a few moments later -- gave the movie a feeling of dangerous vitality and caused a lot of comment. Godard dubiously explained the technique as his way of shortening a film which ran too long. The point is it did give a new kind of kick to the film, as well as make one think again about what cinema itself is. Nobody else makes serious movies that do things like that (unless you count Jerry Lewis... there's Scorsese, but he would do it only with a distinct narrative purpose). It also demonstrates how with Godard, the most intellectual of directors, film is very physical.

I was a little dissatisfied with Eloge de L'Amour (In Praise of Love), his film prior to this one. As always, it had much beauty and provocation, but it felt relatively flimsy and haphazard. Notre Musique (Our Music), on the other hand, I can recommend almost unequivocally. It's the first movie I've seen in as long as I can remember that I didn't want to end. This may have something to do with the way its final ten minutes are set in heaven and that the movie actually is fairly brief -- 79 minutes -- but still, I didn't want it to stop.

The film features Godard himself traveling to Sarajevo to participate in a literary conference, and is divided into three parts: Hell (ten minutes), Purgatory (one hour), and Heaven (ten minutes). (Godard often structures his movies in advance into chapters that seem to help generate content. Apparently his titles serve this purpose too -- the director says that since the sixties he's thought of his titles in advance of the movies.) The "Hell" sequence is a video montage of war and genocide, both "documentary" (war cine-records) and "fictional" (Westerns and War movies). It's horrifying and garish, but the graceful, fast-streaming imagery is also seductive and in a strange way consoling, even soothing. It feels good to consider from the vantage of a movie audience the moving, lyrical, continuous and boundless viciousness of people towards each other. Thus is introduced the main thrust of the movie, which is a consideration of the mutual dependence of certain dualities ("our music"): death/life, darkness/light, negative/positive, imaginary/real, criminal/victim, shot/reverse shot. Godard's whole career could be seen as a meditation on film's mixed identity as documentary and fiction, and this movie is an advanced example of it. The haunting centerpiece is a lecture on "The Text and the Image" that Godard gives a small group in a dark side-room of the half-destroyed city. On either side of that, the story of the movie follows the separate missions of two young Jewish women who've come to Sarajevo, one a French-Israeli journalist -- who wants to bring things "to light" -- and one a suicidal, guilt-ridden Russian-Israeli, moving into the darkness. Both the women, similar-looking in their seraphic freshness, have come to Sarajevo to learn more about the conditions they inherit as Jews. The journalist, Judith Lerner (Sarah Adler), visits a French diplomat (Simon Eine) who hid her grandparents from the Nazis, and interviews an eloquent Arab poet (Mahmoud Darwich as himself). Olga Brodsky (Nade Dieu -- And what's with that last name? Is that a punk-rock name?), who seems both fragile and unshakably committed to her beliefs, talks to her uncle (Rony Kramer) about her determination to kill herself as the only solution possible to her pain and guilt about Israeli treatment of Palestinians.

The viewer welcomes the presentation of the torn-up old graceful city itself, too, with its ruins remaining from the siege bombardments, as well as its regions of ordinary ugly modernity. It's an underrated high virtue of films to present the true feel of a place in time. Notre Musique is a physically lovely movie about irreconcilable oppositions accepted, not complacently, but with compassion and from honest necessity (necessary honesty), as separate faces of the truth.