[to reviews of Godlike]

[to first chapter of Godlike]

[BACK to catalogue listing for orders]

[FORWARD to Hell's "Supplemental Notes" to book]

limited edition hardback cover

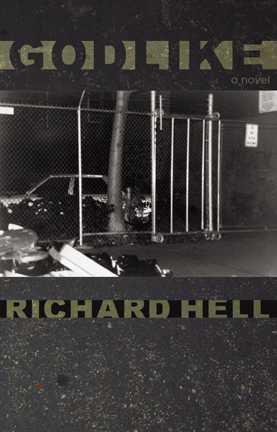

paperback cover

"The imp of the perverse is Richard Hell's co-pilot, and audacity his most enduring habit. But the writer, visual artist and music legend's easygoing virtuosity is what keeps Godlike's crooked path ascendant. Looking back on 1972 from a hospital room in 1997, protagonist and narrator Paul Vaughn recalls falling madly in love with 16-year-old fellow poet Randall Terence Wode, when the latter, newly arrived in New York, shows up at a reading profoundly drunk and scatters the room with insults.

"'I read your latest book and all I can say is that your only virtue is its own punishment,' Wode says to one scribe, telling another that he has 'ruined frivolity for a generation.' More or less overnight, Vaughn's relationship with his pregnant wife disintegrates, leaving the lovers free to drink, drug, fuck, fight and write their way to an oblivion worthy of the notoriously messy romance between the 19th-century French visionaries Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine.

"Those two poets provide a plot skeleton and a few character traits, but they're hardly the only real-life presences. Interpolating Vaughn's recollections and poems with those of Ron Padgett, Eileen Myles and Ted Berrigan (the book's amphetamine-addicted, hovering Buddha), Hell fashions a richly detailed panorama of the East Village poetry scene in the early '70s. Raw, refined, superficially slapdash and impeccably constructed, Godlike deserves its title by becoming a resonant, multilayered work of literature that goes down easily as pulp. What stuns is that it's much more--a poetry-filled novel about poets so introspective, magnetic and alive that even those who think they hate the stuff will find this book irresistible."

--Rod Smith, Time Out New York

"Much ink's been spilled of late on literate songwriters like the Mountain Goats' John Darnielle and Colin Meloy of the Decemberists, but way back, Richard Hell surfaced as a wordsmith even outside the seminal 1977 album Blank Generation. Still, despite verbal acuity and 1984's semi-retirement from music, he's tagged as a lit-dabbling artiste because of work with Television, the Heartbreakers, and the Voidoids.

"Kentuckian Hell (né Meyers) moved to New York to write verse. Accordingly, he kept notebooks and worshipped Rimbaud. In 1979, his 'Slum Journal' debuted in the East Village Eye, mixing texts, graphics, and Poe tributes. In the '80s he founded Cuz (both a lit journal and a press), through which he's published Dennis Cooper, Rene Ricard, Eileen Myles, and Nick Tosches. His own output includes poetry collections as himself and as Theresa Stern (a gender-bent collaboration with Tom Verlaine), a novel (Go Now), and a textual/visual miscellany (Hot and Cold). He's back with Godlike, his second novel and strongest piece of writing to date. It's no wonder Hell grows testy when critics refuse to see him sans bouncy stage presence.

"He prefaced a recent Godlike reading by mentioning that one too many scribes had misread Go Now as memoir. To prove he could write fiction, he jettisoned Go Now's womanizing-junkie angle for a moving, scathing novel about the 'love' of two male poets, the married 27-year-old Paul Vaughn and 16-year-old Kentucky prodigy Randall Terence Wode a/k/a 'T.'

"The two inhabit '70s downtown NYC dives (memorably, T. pisses in a champagne glass at Max's Kansas City), crash collating parties, haunt readings, and sit alone in T.'s dinky apartment collaborating on poems and chewing scenery as self-professed flaneurs, 'godlike philosopher poets' of the L.E.S. 'languorously sipping their fermented grain as they spun ideas and mental- sensual constructions of life-language in the air for the pleasure of their own delectation.'

"Steering clear of narrative niceties, Godlike offers fragmented reminiscences of the middle-aged Vaughn. Pompous, unsure, he recounts his relationship with the deceased T. via interwoven letters, diaries, poems, essays, and a memoir-novelette he started in 1997 when spending time in a mental hospital for a nervous breakdown. In his 2004 prefatory letter, Vaughn describes T. as 'a scumbag,' but the enfant terrible eventually emerges as the more likable (and talented) of the two, and questions of their 'love' arise. (Hell convincingly writes in the different characters' poetic voices.) Vaughn's an unreliable narrator, sure, but as Hell puts it, 'poets aren't supposed to be beautiful or sane. Shaggy, itchy, preoccupied, mal-educateds. It's a dirty and stressful and anti-social calling.' Well, like punk rock.

"Punk/lit parallels exist: Like T., Hell was born in the Bluegrass State, and T. resembles the thin, pouty Hell and his 'short and ragged' mid-'70s hairdo, but comparisons to Rimbaud also make sense. One of the best descriptions of T. (and perhaps Hell) takes place when looking at the books he grabs from Vaughn's shelf: 'a Bill Knott, a Borges, a Frank O'Hara, David Shapiro's skinny little January, and Ron Padgett's Great Balls of Fire.' (The moment evokes Thomas Bernhard's Extinction, wherein Kafka, Musil, and Bernhard himself are assigned reading.)

"Rather than fish for Hell biography, readers ought to riff instead on tumultuous (Paul) Verlaine and Rimbaud. Vaughn's pregnant wife, Carol, makes cardboard appearances. T. drops poetry for South America, shadowing R's time spent as a trading company agent in Africa and the Middle East. There's no amputated leg, but like Verlaine, Vaughn gets hold of a gun: 'The freedom of youth! He was hardly hurt at all.' (Both Verlaine and Vaughn serve 18 months in jail, find religion.) Careful readers will uncover bits like a nod to a priest's interruption of Verlaine's incarcerated confession: 'You've never been with animals?' Here, T. asks: 'Did you ever try to fuck something not human?' Turns out he did, 'a little pony.' Which makes sense: Vaughn's eternally horny ('I never had that gay thing about boys' butts really [while I do like women's]'), and after he and T. tie up a female versifier from the Poetry Project, he enthuses: 'The nicest people love a chance to be sexually used without worrying about it.'

"Godlike often subscribes to Mallarmé's symbolist ideals as well as the late-night amphetamine feel of Ted Berrigan's Sonnets. Much of the book's composed of Vaughn's proclamations and T.'s outbursts retold by Vaughn. Everyone from Liv Tyler to Egon Schiele earns memorable analysis. He waxes eloquent on cartoons and comic books as paradisal eternity. Birds and God show up hand in hand with Bresson, Dante, and J.Lo. Not merely class clown, Vaughn posits moving thoughts on aging with a touching romanticism. Unlike T. ('The positive anonymity of leaving is preferable to the negative anonymity of loving'), he's a firm believer in love: 'Is it possible that one other person on earth can render the rest colorless by his absence? Yes, of course.'

"Through it all, Godlike also functions as a downtown guidebook circa 1971, inlaid with road maps to Veselka, Washington Square LSD, and L.E.S. versus the 'cheesy media/marketing language' of the East Village. More importantly, the text's a literary treatise stitched with shards of Padgett, an attempt to locate a gallant geometry verifying love's reality, and proof again that Hell would have carved a smashing oeuvre even if he'd opted to remain plain old Richard Meyers."

--Brandon Stosuy, The Village Voice

"'In the future,' one reads early on in Godlike, 'all poetry will be translation' -- a line that, itself, sounds suspiciously like a translation or at least a quotation of or allusion to a text that already exists somewhere (though perhaps not in the work of Mallarmé, whom Hell's narrator has just been discussing). Even this fact of having a narrator -- something that in most writers' hands is just a blandly self-evident fact of conventional technique -- turns out to be something like a fact of translation: Narrator and author paraphrase or reinterpret each other between the lines. This 'novel' -- Richard Hell's second, following Go Now, 1996, and the 2001 collection of prose pieces and poetry, Hot and Cold-- is hardly written the way a novelist would write it. It is altogether a poet's work.

"What a poet's novel needn't be, thankfully, is 'well-written.' Nothing here of that neurotic polishing of sentences into bland smoothness that characterizes most of what the publishing industry calls 'literary fiction.' This prose, like poetry, moves at the speed of thought and just as awkwardly. Its jangly, nervous, unpredictable music, slipping abruptly between the first person of memoir and a storyteller's more distanced third person, is thrillingly thin-skinned. Anyone who ever doubted that Hell could achieve with words alone something as compelling as what he's done with words and music together (Blank Generation, 1977; Destiny Street, 1982; Dim Stars, 1992; Time, 2002; Spurts, 2005) will have to think again.

"To put it bluntly, Hell has translated the story -- maybe it would be better to say, the legend -- of Paul Verlaine's affair with Arthur Rimbaud starting in 1871 into the idiom of scuzzy Manhattan in 1971. The 16-year-old provincial hothead -- here called Randall Terence Wode, familiarly 'T.' -- who arrives in the big city knowing that 'to give offense was his mission, his meaning' inevitably recalls the Richard Meyers, as he still called himself then, who turned up in New York at about the same age a few years earlier. But as much as the author of Godlike might have been tempted to see his younger self in the teenaged poet invading the metropolis, he gives the story's telling (and the reader's empathy) over to the older married poet, Paul Vaughan, the perplexed witness of this manipulative and unkempt meteor.

"'I may be in the loony bin but I am not an unreliable narrator,' Paul insists. His seemingly self-contradictory statement is worth taking seriously. For one thing, the book doesn't have enough plot to make any tricky narrative devices necessary. The book is compulsively readable but what moves it forward is the urgency of rumination on a series of encounters, most notably of course the fateful one between T. and Paul but not only that one: Figures emerge out of the background and then disappear, their advent being without particular narrative consequence yet of enigmatic spiritual significance. In fact, the question of whether a life-transforming encounter really has any upshot is one that lurks behind the entire book. That eventually T. will have to get bored with Paul, and Paul will shoot his young lover, is a result, not so much of Hell's formal decision to echo the Rimbaud/Verlaine story, as of internal necessity the lovers have to short-circuit a self-contained dyad that can only keep leaking away emotion as it feeds only on itself. Boredom, in so many words, though articulated with such insistence as to feel deeply sexy.

"Yet always there is the possibility that this monotony will flare up with some illumination. 'Most of the time we are only a little alive, like a book in an obscure language,' T. tells Paul. To love someone is to translate them and thereby kindle their life again for a while. Which must be why, as Paul declares, no longer couching his recognition as a prediction for the future but as a present fact, 'All poetry is translation!' And Hell has practiced what Paul preaches. When T. tells his anomic friend Catherine that she looks like she's been out in the sun, 'you could almost be someone else, the way your face is like switched on so the...freckles are highlighted,' and she responds, 'I am someone else,' the reader must know that Rimbaud's famous words are being filtered through hers, and hers through his. Likewise, when Paul's buddy Ted shows him a new poem he's written, one instantly recognizes it as a transposition of Frank O'Hara's 'To the Harbormaster,' as if the fictional poet were unknowingly translating an American poem into another American poem. The whole novel is a tissue of citations, renderings, transpositions, versions. Every life is woven from bits of lives that were lived before. Does this make them less real, or does their reality consist just in this?"

--Barry Schwabsky, Galatea Resurrects

"Richard Hell is of course the former singer-songwriter-bassist for the early New York 'punk' bands Television, The Heartbreakers, and the Voidoids, and later musical assemblages such as the Dim Stars. Always a fascinating lyricist, he has in the last decade or so forsaken music-and an on-and-off-again acting career-and turned his attentions to the written word almost entirely, building himself a very interesting, if underappreciated, career as an essayist, critic, poet, and novelist.

"Hell's first novel, GO NOW, released in 1996, can probably best be described as a flawed effort that manages to succeed in many ways despite itself. It is the story of a cross-country trip taken by a down-and-out, and hopelessly strung-out rocker named Billy Mud and his French photographer former-girlfriend, Chrissa. As Billy's musical career and life are hitting a serious trough, Chrissa uses her connections to get them both a book deal, the premise being that they will fly from their homes in New York to Los Angeles to pick up their backer's 'fire-colored '57 DeSoto Adventurer' and then drive it back to New York, for the purpose of later creating a book about their experiences along the way, with Billy writing the text and Chrissa supplying the photographs. This trip back to New York turns out to be a strangely under-described leapfrog from city to city, during which Billy and Chrissa find and lose each other again on more than one occasion, while Billy spends most of his time scoring, or being sick because he cannot score, heroin.

"While there is some wonderful writing in this book (especially in its early chapters), where Hell lays down some jarringly spot-on descriptions of and insights into the artist-junkie's lifestyle in late-twentieth-century America, it is ultimately undermined by its gimmicky plot and the lack of interest its author eventually seems to show in his own narrative (it is as if Hell realized halfway thru things that his basic premise was not working very well and simply did not have the heart to delve into it any further than absolutely necessary). In the end, we are left with huge chunks of a truly fascinating addict's memoir attached to the wobbly scaffolding of just another silly road-trip novel.

"I am happy to report that GODLIKE, Richard Hell's second novel, is an affair of a much higher order, both as a technical piece of writing, and more importantly, in the depth and wisdom of its tale.

"In this novel, Hell basically retells the story of the doomed love affair between the great nineteenth-century French poets Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, recasting them as American post-Beat poets who come together in New York City in the early 1970s. Paul Vaughn (Hell's Verlaine stand-in), though he hangs out deep in the heart of New York's underground poetry scene of little mimeographed magazines and drug-soaked bohemianism, is also a married man, who goes home at night to a life of middle-class comfort, mainly because of his wife's family's money and connections. This more mainstream half of his life is quickly shattered, however, by the appearance of a young poet named Randall Terrance Wode (most often simply referred to as 'T'). At sixteen, T has flown from the stunting sterility of suburban America to the more stimulating environment of New York City. Having written his poet hero Paul in advance (and out of the blue) of his plan, Paul encourages his young fan to track him down once he is in the city, which T does, in arrogant, blustering, and brilliant fashion at a poetry reading featuring what seems to be a large number of New York's alternative poetry elite. Paul immediately falls violently in love with T, forsaking his pregnant wife on this very first night for the burning privilege of sucking T's dick and generally basking in the genius and passion that the younger poet constantly sheds like sparks from a crackling fire.

"This relationship is not entirely a one-way street, however. Paul is T's gateway into the world of poets, and for a time his necessary partner in mind-opening (and bending) experiments with homosexuality, various drugs, and a poet's lifestyle that finds its meaning in pushing things to their emotional, physical, and financial edge. But though T is brilliant, he is also a peculate child, and therefore cannot return or even understand Paul's love; and so Paul ultimately becomes little more than fodder for T's insatiable need to experience, his need to move beyond certain feelings and beliefs in search of his own destiny. Because of this, Paul is eventually forsaken by T, but not before a wild affair of bittersweet meaning is paraded before our eyes. Not that Paul is anything close to a complete victim; he truly understands T and what he is getting into. He also has his own agenda of need fulfillment, which he is not shy about putting into play, and most importantly, understands certain things that T, with all his intelligence, does not-mainly that youth, though it is amazing, is also short-lived and limited in its vision, and finally that 'love is real.'

"Those familiar with story of Verlaine and Rimbaud will easily recognize the grooves and textures of this novel, and those who are not will probably feel a sense of déjà vu anyway, as the dynamics of Paul and T's impossible love accurately reflects so many a doomed relationship in literature-and more importantly, in life. Indeed, one of the most interesting virtues of this book is how its familiar story works to its advantage. Freed from the necessity of having to labor over the mechanics of his plot, Hell is able to paint in broad, almost impressionist strokes, which not only lays bare the inherently diaphanous nature of his main subject matter (poets, poetry, and of course, romantic love), but also allows him to describe the more surface level aspects of New York poetry scene of the early seventies, and the time and place in general, in language which is often both shimmering and evocative without ever being soft or lush.

"This story's evocative nature also owes a great deal to its structure. Though told from Paul's point of view, the novel does not follow the standard first-person narrative, but shifts back and fourth between fragments of Paul's abandoned novel about T and excerpts from his notebooks, many of which are written from the mental hospitals in which Paul apparently often finds himself in the years after his time with T has ended. In less skillful hands, such an approach could easily become unwieldy and/or pretentious; but with Hell it becomes the instrument he uses to truly capture the voice of his aging poet, both thru "Paul's" prose, and thru the poetry Hell writes in Paul's name (Hell's skill as a poet as well as his knowledge of poetry serves him well throughout this work, as 'T's' poetry also appears and other real-life poets are quoted liberally).

"Though GODLIKE updates the Verlaine-Rimbaud story in a sure and meaningful fashion, and also brilliantly captures the feel of New York poetry scene in the early seventies, in the end, what reveals this work's true worth is that it transcends both its love-story framework and the time and place in which it is set and shows the broader and deeper reality of being an artist in a society that does not value such insights. Basically, GODLIKE is a wonderful novel on all levels, that due to the underground nature of its author's reputation and its graphic and unapologetic descriptions of homosexuality and recreational drug use, will probably languish as a cult read-at least for the time being. However, if this country ever decides to move in a more humane and compassionate and less judgmental direction, GODLIKE will no doubt come to be seen as the American classic it is."

--Rob Woodard, Burning Shore Reviews

"'The Creator expressed his gratitude by a movement of the head. Oh! You will never know how difficult a thing it becomes to be holding the reins of the universe! Sometimes the blood rushes to the head as one strives to wrest from nothingness a last comet with a new race of spirits.'

-- the Comte de Lautréamont in the third Canto of Maldoror

"Rudimentarily speaking, Godlike is an updated version of the relationship between the writers Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud. As Hell’s reinvention, it is a story of the 1970’s East Village as told in 1997 by Paul Vaughn (Verlaine). Through a series of diary entries, letters, poems, and an essay about Mallarmé and translation, he speaks of his torrid, yet inspired, involvement with a young poet Randall Terrance Wode (Rimbaud) known throughout this novel as T.

"Structurally, it pretends to be a pre-first draft of a memoir as novelette in the form of published notebooks. The second-hand tale of the two poets is used adroitly as an unraveling tapestry onto which Hell weaves his own poetic color and shape scheme. Poetry doubles as the landscape and the centerpiece throughout. The book has a divine experimental stink wafting from it: an exotic perfume that makes no attempt to cover up the reek of day-old piss and puke. It’s irresistible!

"Music (what Hell was famous for in the punky late Seventies) has little apparent connection to this arrangement of notebooks. Much more obvious is Hell’s involvement with filmic ideas. Paul Vaughn says several times that this is actually a film. He refers to Jean-Luc Godard twice.

"Godard said in one of his succinct moments: 'I prefer simply putting things side by side.' This is the sense I get of Hell constructing this book: that it was built up over time, as if he polished stones, leaving some edges jagged, and assembled them into a lovely (and lonely) cinematic architecture of ruins. In the long run, putting things side by side becomes something much richer than mere comparison.

"As Paul moves through his story, it becomes clear that his is an obsession-stricken mind, an over-medicated mind that is not just a bowl of glittering strawberry Jello. Paul’s mind is actually the reason to read this book. He has never finished processing the effect that his infatuation for T. has had on him, because he has never been able to stop feeding off of T. or his inspired image of him. That struggle has made him the writer he is now and an adventurous thinker. At sundry times Paul’s mind flickers through a montage of rapturous and inconsistent thoughts that are fastened end to end wildly, but with great care. Included are poems by T., Paul, and other fictitious poets that further extend Hell’s imaginative existential musings.

"The title Godlike refers, of course, to the sixteen-year old T., whose divinity is based on an array of revelations he imparts to the ten year older Paul over the course of the book. Paul is intoxicated by weeks of psychedelic, drunken sex and the dirty boy’s fresh, unflinching take on the world around him. The casual cruelty through sex with T. in front of Paul’s pregnant wife and the icky blissful encounters that follow create in Paul an awareness of freedoms he has never known. He helplessly continues a relationship with the boy. Rude T.’s audacious commentary flows out towards any signs of inappropriate sentimentality. But instead of converting Paul from his weaknesses, T. uncovers more and more of them as their doomed relationship is played out in the most squalid circumstances. Paul’s forlorn sentimentality appears often as he writes and Paul is well aware that T. would despise its presence.

"Being Godlike is also an attribute of celebrities, especially film stars. There is an early reference to Bette Davis that makes clear T. will be an unbearable, essential star in the poetic universe. He is an actor as well. He adores equally the unpopulated countryside and the actress Tuesday Weld. Paul depicts T. crying as he cores an apple. Paul does this a few times, he attributes the humanity he wishes T. would show in scenes where Paul sleeping and can’t really know what T. is doing.

"The hole that T. has left in him has grown so cavernous after all these years that a return to Catholicism teeters towards fragility more than strong faith. As a somewhat used-up bohemian in his early fifties, Paul still drinks and takes medication in the hospital where he tries to recover a few weeks every year. He finally admits that nothing is left inside him except the love he was never able to shake or shape into anything except a few poems and these notebooks.

"I am reminded of La Vent da la Nuit (Nightwind), a film by Phillippe Garrel, another poetic visionary of the French cinema (not as well known as Godard). In it, Garrel has created a marvelous character, Serge. He exudes an attractive pessimism set into motion by the passing and haunting of a great love. The adored image in the film is a simple photograph that fixes the beloved in a glorified past. This idealized love traps him in a perpetual cycle of remembering and distracting himself from remembering.

"In Godlike, however, Paul is not quite stuck in the past because he is aware of the changes the intervening years made in him. He speaks constantly of time and death, what his own identity is in relationship to those around him, and how these things are determined by the imagined past and future. He finds that surviving this long is a good thing though the transition into old age will not be an easy one for him.

"By outliving his youth and still remaining in the shadow of T., Paul is now capable of being GODLIKE himself. He has, after all, built and controlled the world of this book, including his portraits of T. and himself. For quite some time, he has been determined to set down what T. was (to him) and what he himself has become.

"It is fortunate that Hell loves playing in language enough to turn his mud pie into a soufflé. He deftly invokes the spirit of a number of precocious French poets in their smuttiest romps as well as their loftiest visions (not only Rimbaud and Verlaine, but Baudelaire and Lautréamont, too). Occasionally, he echoes the systematic antics of that absurd gang of writers, Oilipo. And there are allusions to numerous poets of all sorts if you take the time to find them.

"Hell can’t help making phrases that stick out like the uneven planks on a Boardwalk after dark. Sometimes they sting like a Canker sore that flares up on the underside of the tongue. Whether his words are depraved, delirious, or bound up in what makes a human 'be,' Hell’s language is a dank field of heady poppies growing in asphalt. Take the time to trip through it."

--Rob Stephenson, Velvet Mafia

"Don't go for a Jonathan Franzen monster; you'll want the elegantly slim novel Godlike by Richard Hell. The blank progenitor holds the previous distinction of writing the best junk novel ever (Go Now) and it's been far too long a wait for his second major work. Godlike, a fictionalized poetry-Babylon set on New York's Lower East Side, opens: 'The weather was like a pornographic high-fashion magazine. But Raw's Drink was a gutter derelict in it. The room was see-through brown broken by a debris of battered tables and cluttered walls. There was a little clearing in the far corner where a stalk of microphone stood leaning thinly.' It might be the saddest description, ever, of a poetry reading but whatever sadness is in the book is balanced by Hell's glass-shard-sharp sentences and apocalyptic imagination."

--Brian Joseph Davis, The Toronto Eye

"Poet and punk pioneer Hell's lyrically melancholy second novel (after Go Now), set primarily in the East Village circa 1972, honors decadence and dissolution and celebrates art and angst in a compelling if unsettling story of 27-year-old married poet Paul Vaughn's ('I'm not really a faggot. I just have a queer streak') transcendent affair with a 16-year-old. Would-be poet Randall Terence Wode ('T') is 'a rampaging adolescent' whose 'bony boy's buttocks' become, for a brief time, the center of Vaughn's physical desire, and whose brash spirit is, for 30 years, the core of Vaughn's emotional universe. The novel's wrenching account of a memorable love, peppered with poems (some original, others by James Schuyler, Ron Padgett and others), skips between the months of the older poet's affair with the cocky young Kentucky runaway and, decades later, the month of Vaughn's most recent institutionalization for psychiatric observation. But Hell's prose, alternately explosive and tender but always charged with rewarding humanity, ably propels the story. By no means a mainstream effort, this gritty novel will find readers in the demimonde of poets and people who read them, and among those who appreciate how artistry and sexuality can fuel each other."

--Publisher's Weekly

and check these blog reviews:

I want to make what I know of R.T. and that time into a book so that it won't be gone. I don't have the best memory in the world but there is no reason I can't produce a story as close to true as it would be if these things happened yesterday. It will just have mixed into it what I have become across twenty-five years, but that includes what I've learned, and at least I can say with certainty that it's written with love and without any hidden purposes or self-censorship.

Those are more or less the first words in the first of the notebooks I filled when I was in the hospital in 1997. I planned to write about T. in the form of a novel. I wrote other things in the notebooks besides my story of T., too: letters, diaries, poems, even an essay. Now I've accepted my editor's encouragement and made this book out of all of it.

As an account of T., it will have to do, because T. is gone and only he could offer a memory to compare. I've known for a long time the meaning of the deaths of friends. It's losing oneself! T. took me with him, but I've been what I can, and I want to present my him before it's too late for me too.

Look, he was a scumbag. Nearly everybody hated him. He didn't care! He insisted on it. That's the beauty of it. But it's important that you not like him either. If you like him, you don't understand him. To give offense was his mission, his meaning. This was part of his failure, the impossibility of him; I don't advocate it--it's just what he was. I do maintain that it's interesting. But then a good writer can make anything interesting.

It makes me think of movie stars. People say James Dean was the same way, mean and arrogant and competitive. And I remember having this revelation watching Bette Davis on-screen one time. That everything that was magnificent about her in the movie would be impossibly obnoxious in the same room with you...

Paul Vaughn

NYC, 2004

Paul felt affection for the poor poets, his family. He probably liked them more than anyone else did. He was popular for that.

Tonight's reader was Tom Bennett. Tom was a filthy drug addict who was too smart for his own good. His face was like a monkey's carved from a blond wood doorstop wedge, he was going bald, and he wore reddish whiskers that looked like pond scum. He never stopped talking and he considered himself a Buddhist. Whatever else, he was in his element at Raw's this night, and it was heartening. He was a messenger and Paul was mentally gorging on it. "God made everything from nothing, but the nothing shows through."

Paul played a favorite mental trick for enjoying poetry readings and imagined the reader had died long ago.

The reading ended, and everyone drank on, and the room got noisier. People went out into the air and smoked grass together and came back. Paul saw the kid. He planned to find him but hadn't gotten around to it when he sensed the attention shifting in the crowd. The kid'd gone up to three different poets in the room and told each what he thought of him. He told Bill Miller, "I read your latest book and all I can say is that your only virtue is its own punishment." He told Barret Combs that he'd "ruined frivolity for a generation." Then he gave each of the poets hand-copied examples of a new poem and told them that they could suck his cock for $20. He arrived at Paul, and just as Paul realized who he was the kid introduced himself. He was the boy who'd sent him a letter a few weeks before. The letter had read:

Mr. Vaughn! Sir!

I write to you most humbly, most presumptuously. I am no one except that I am a poet. And it is because I am a poet that I eat up your books. And that is why I write and enclose the pages you find here. I hope that you will respond to them.

I'm going nuts in this nowhere. Used to be I could twist in my misery and big time lusts, sweating, and the breezes of these suburban streets would cool me a little, the fruity sunsets would bring me something, as would old literature, but now I know too much! One must always move on. (It is not important to live.) I'm rotting here! I will come to New York. Especially since I know of you.

Do you know what I mean that I am no one except that I am a poet? I will explain so that you cannot misunderstand. I do not want to be anyone. I have nothing to protect! I want to see and be seen through. I am given to see and I see aloud. It is necessary that "I," that cowardly imposition, be discarded, in order that nothing interfere, that nothing interrupt, that nothing pollute what speaks. It isn't pretty! But it is poetry and all we know of--of--. I know you know what I mean.

Have mercy on me.

Your admiring little bro,

Randall Terence Wode

Paul had written back and told the kid he should come to New York and to call him when he got there.

"I am drunk," the boy said.

"Yeah?"

He lowered his voice again. "Come outside and walk with me."

They left the party behind and the air outside was a nice surprise. The presents kept coming, piling up around them as they walked. Paul got breathless and aroused.

R.T. told him his big ideas. He said honestly there were only two or three poets and that he himself was first among the living, with the possible exception of Paul, though Paul was in danger of going slack. He talked of how the literary was sacred but the literary was shit. That the poets' poor knowledge must be advanced in life for poetry to be real. That the poem is everything, but incidental--it's shit and come, it's tracks and mirrors, hair, snot, ricocheting beams. It's nothing, but it's all we get and if we will be receptive it's the thing itself, the nothing itself, and what else is there to desire, want, have, be, and it only follows from delerium, which is just ordinary life. "No big deal," he said, and it was true--Paul'd heard it before (though he hadn't seen it)--, "You want to kiss me, don't you." He took Paul's hand and pulled it to him and pressed the palm on his crotch.

They'd stopped and T. was shuffling Paul back toward a dark building wall on East 3rd Street. Paul's heartbeat was out of control. He was taller than T. and he grabbed T.'s ruffled head and bumped his mouth on his. The oddness of male on male was sexy. They almost fell over but the wall got there just in time. The mouth was a scooped-out thing that felt unreal; Paul couldn't adjust, he was still too apart from him, but he wanted to feel T.'s cock through his pants and when he did that it went really real for a moment before they separated again.

Paul just wanted to run his finger along the crack of T.'s ass, and T. let Paul turn him to the wall and do that. He reached under and T.'s cock had gotten harder and he squeezed its base through T.'s pants. T. gave Paul charge of himself there for a moment, and Paul took advantage of it by pulling T.'s shoulder to turn him, kissing him once again, and it felt closer to a kiss. Paul started them walking back along the street. He wasn't going to hurry or let T. think he was at his mercy. It was better to stretch it out anyway.

"So how does it feel to be a faggot?" T. asked.

"What?...Uh...So far, so good."

"But you always have been."

"Whatever you say..."

They stumbled into Paul's rooms on Bank Street at about 4:00 A.M. In the house everything was stagnant and half-size, defensively smug. When the pregnant wife came in, Randall threw up. She screamed and stuttered. She looked inappropriate, like a mangy zoo creature in a fake habitat.

"What a stink," T. said, "That stuff smells... Let's try to go to sleep." He looked at Paul and suggested, "Why don't you slap that thing."

Paul lurched towards his wife and she fled. Paul turned and grinned as if he'd just scored a goal, started back to T. and slipped in the vomit, then fell to his hands and knees. He laughed. "Ugh." It wasn't too bad. T. sat down in an armchair as Paul got up and put one foot in front of the other toward the kitchen around the corner. When Paul came back with a large wet terrycloth, T. had his penis out and was idly playing with it. As Paul kneeled over the pool of vomit he looked at the penis and then at T.'s face. He put his own hand down his own pants, but no, he wanted to wipe up the mess. The smell stung, but for a second he liked it: scent of death rot, home, was the sticky inside of his own asshole when he stuck a finger in it masturbating. He was getting a kind of hardon, but he threw the towel over the vomit and tried to wrap it up. His wife scurried through the room holding a soft little overstuffed bag. When she saw them she recovered her dignity for a moment in amazement, and for that moment Paul sank and groaned inside but T. was tougher, and she retired from the house with a sad squeal.

Paul crawled over and pulled T.'s cock in between his lips. He filled his mouth with it most gratefully and T. gazed at him with contempt that was tremendous and delicious. Paul was still a little bit ashamed and that's what made the cruelty right and the perfection of it pooled them together. After all, T. was Paul's admirer, and T. was the grateful one, for being allowed to be mean with love. The world was young.

And in the morning the sun found them out on the floor of the little parlor entangled and gritty, the faint death-smell of the half-digested food and alcohol mixing with the brute light; bodies God's idle graffito.